Picture Postcard History

Court card of Worthing postmarked January 14, 1900 and published by The Pictorial Stationery Co. Ltd. of London (Number 1144 in the list compiled by George Webber for Picture Postcard Annual, 1997) .

During the closing years of the nineteenth century, sending picture postcards became something of a craze in continental Europe, particularly in Germany. Britain lagged far behind its continental neighbours because of restrictive Post Office regulations. Only when the regulations were finally eased did postcards become popular in Britain as a means of communication.

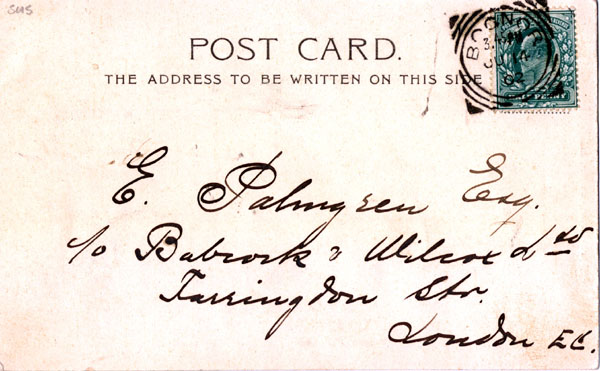

Post Offices in Britain started selling plain cards with pre-printed half penny stamps as early as October 1870. However, the postal authorities refused to permit adhesive stamps on cards, and this discouraged private firms from printing their own cards with added pictures. Any privately produced card had to be sent through the post enclosed in an envelope at full letter rate (1 penny). It was not until September 1894 that the British postal authorities bowed to public pressure and agreed to accept cards for delivery bearing adhesive half penny stamps. Even after this concession, there were still major obstacles to overcome before picture postcards could be sold in large numbers. Post Office regulations initially dictated that the largest cards that could be sent at the halfpenny rate were so-called "Court Cards" measuring 3.5 by just 4.5 inches. Anything larger had to be sent at letter rate. Even more irksome was the rule that only the names and addresses of the intended recipients could be written on the backs (or stamp sides) of cards. All correspondence or greetings had to be written on the front, restricting the space available for pictures.

Undivided back on a Bognor card published by Valentines of Dundee

In November 1899 the British postal authorities finally relented and agreed to allow cards measuring a full 3.5 by 5.5 inches (the modern norm) to be sent at the halfpenny rate. They continued to insist, however, that nothing but the names and addresses of the recipients could be written on the backs of cards. As before, pictures and correspondence had to share the card fronts.

In January 1902, the regulations were still further relaxed to allow postcards to have a dividing line down the middle of the back separating the correspondence space from the address. The fronts of the cards could at long last be used exclusively for pictures. With this new concession, the modern-style "divided back" postcard was born and began replacing the full-size "undivided back" cards that had come into use following the November 1899 decision.

The introduction of the divided back triggered an explosion in postcard sales. In a pre-telephone age, picture postcards offered a cheap and effective means of keeping in touch with friends and relatives. Moreover, they were often attractive to look at, and Edwardians, particularly ladies, took to collecting postcards in large numbers. In the year ended March 1903 the Post Office is estimated to have delivered about 39 million pictorial cards, three years later the number is thought to have risen to 264 million (George Webber, Picture Postcard Monthly, July 1990, p.8). After this a decline set in. An estimated 190 million picture postcards were posted in the year to March 1910; by March 1914 the annual total had dropped to an estimated 71 million. Of course, actual sales of picture postcards would have been much in excess of these figures because the Edwardians purchased cards in large numbers not only to send through the post but also to keep as collectibles. This is one reason why so many of the cards that survive today are postally unused - they were stored in owners' albums to be admired and discussed.

The soaring demand for postcards led to a huge increase in the number of postcard publishers, and cards were issued covering a vast range of subjects - local views, parades and processions, railway engines, ships, actors and actresses, cats and dogs, military exercises and so forth. Comic cards were particularly popular, ranging from the frankly vulgar ("the saucy seaside postcard") to those offering more subtle political and social comment.

The Great War in 1914 brought a rapid end to the "Golden Age of Postcards", as it was later named. Everyone expected a quick victory and hoped the troops would be home by Christmas, but the war dragged on and casualties mounted steadily. Almost everyone lost a friend or relative, and the national mood became ever more sombre. Sending postcards came to be seen by many as an inappropriate frivolity, and sales plummeted. In June 1918, even before the war ended, the postage rate for cards was doubled, further depressing sales. The spread of telephones after the war helped to reduce the market for postcards even further.

During the war many postcard publishers went out of business, but when peace returned new publishers tried their hand. Some quickly failed, but the more enterprising and successful were able to maintain fairly steady sales until the Second World War. With the resumption of hostilities the majority of publishers were forced to give up because of a rapid decline in sales and shortages of printing materials.

After the Second World War, a few new publishers attempted to enter the postcard business, but trade continued to decline, and today only a very small number of firms are left, such as Judges of Hastings and Salmon of Sevenoaks. Increasingly, the mobile phone and the E-mail have supplanted the postcard as a means of communication, but paradoxically people are once again keenly collecting postcards as a hobby, particularly old cards because they provide a valuable record of the past.